Once again, although I was established in the studios I found myself hitting a brick wall with regards to changing jobs. It was next to impossible to make the transition into 'sound' because of the trade union situation - NATKE (projectionists) and ACTT (film technicians). Unless you had a relative in the business (or there happened to be no ACTT members available for work) there was little chance of making the move. The only way to ease across was as a Trainee Boom Assistant, as you didn't necessarily have to be a member of ACTT for this job. So I went to the Sound Department head, Cyril Crowhurst, to ask him to give me a break and luckily for me it worked.

In May, 1969 I started work on J & K Stages, which were only three years old, on the TV sit-com "Up She Goes" (later to be titled "From A Birds Eye View"). The same day, Billy Wilder  started shooting the film "Private Life of Sherlock Holmes" on the newly constructed 'Baker Street' set on the back lot. At lunch time I went on the set and chatted to the sound crew. The sound mixer was Jock May (who was Hammer's main production mixer during their golden period at Bray), and the Boom Operator was Charlie Wheeler. I was warned that he was a tough Union man to work for, but I got to like him a lot and he taught me much about the job. The leads, Millicent Martin, Patte Finley and Peter Jones were all very friendly. Likewise, Ralph Levy, who was a superb experienced TV Director. Jeff Seaholme, famous for the Ealing Films, was our camera operator and I got along with him really well too. Unfortunately, he had a falling out with the Director and was dismissed. I told him I was sorry to see him go and on his departure he gave me a whole pile of back issues of "Films and Filming" which I still have.

started shooting the film "Private Life of Sherlock Holmes" on the newly constructed 'Baker Street' set on the back lot. At lunch time I went on the set and chatted to the sound crew. The sound mixer was Jock May (who was Hammer's main production mixer during their golden period at Bray), and the Boom Operator was Charlie Wheeler. I was warned that he was a tough Union man to work for, but I got to like him a lot and he taught me much about the job. The leads, Millicent Martin, Patte Finley and Peter Jones were all very friendly. Likewise, Ralph Levy, who was a superb experienced TV Director. Jeff Seaholme, famous for the Ealing Films, was our camera operator and I got along with him really well too. Unfortunately, he had a falling out with the Director and was dismissed. I told him I was sorry to see him go and on his departure he gave me a whole pile of back issues of "Films and Filming" which I still have.

started shooting the film "Private Life of Sherlock Holmes" on the newly constructed 'Baker Street' set on the back lot. At lunch time I went on the set and chatted to the sound crew. The sound mixer was Jock May (who was Hammer's main production mixer during their golden period at Bray), and the Boom Operator was Charlie Wheeler. I was warned that he was a tough Union man to work for, but I got to like him a lot and he taught me much about the job. The leads, Millicent Martin, Patte Finley and Peter Jones were all very friendly. Likewise, Ralph Levy, who was a superb experienced TV Director. Jeff Seaholme, famous for the Ealing Films, was our camera operator and I got along with him really well too. Unfortunately, he had a falling out with the Director and was dismissed. I told him I was sorry to see him go and on his departure he gave me a whole pile of back issues of "Films and Filming" which I still have.

started shooting the film "Private Life of Sherlock Holmes" on the newly constructed 'Baker Street' set on the back lot. At lunch time I went on the set and chatted to the sound crew. The sound mixer was Jock May (who was Hammer's main production mixer during their golden period at Bray), and the Boom Operator was Charlie Wheeler. I was warned that he was a tough Union man to work for, but I got to like him a lot and he taught me much about the job. The leads, Millicent Martin, Patte Finley and Peter Jones were all very friendly. Likewise, Ralph Levy, who was a superb experienced TV Director. Jeff Seaholme, famous for the Ealing Films, was our camera operator and I got along with him really well too. Unfortunately, he had a falling out with the Director and was dismissed. I told him I was sorry to see him go and on his departure he gave me a whole pile of back issues of "Films and Filming" which I still have. At this time Nagra quarter-inch Swiss tape recorders were steadily taking over the British Film Industry as the standard for production sound recording. Since the introduction of magnetic film at the beginning of the 50's production sound was either recorded onto 17 1/2 or 35mm single stripe magnetic film. "Up She Goes" was recorded onto 35mm single stripe magnetic film. The audio was picked by a D-25 microphone onto a Fisher 'boom' and was routed through a small 'floor' mixer and then sent to a small 'monitor' room located on the side of the sound stage.

My job as 'Boom Assistant' was to come on to the stage in the morning at least an hour before the crew arrived and lay cables connecting the boom to the mixer and the monitor recording room and a cable from the mixer to the camera. Next, I had to wheel the Fisher 'boom' on to the stage from the sound department. Thr Fisher boom was an instrument on wheels with a platform to stand on and an arm that extended several feet and at the end of it was affixed the microphone. The operator could control with ease the position of the microphone over the actors by extending the arm and swivelling the microphone to the correct angle of the emitting speaking voice. The wheels were like small car tyres and could extend or contract to fit through narrow areas. They had to be extended when being transported to and from the stage. Every assistant had had the harrowing experience of tipping the fragile boom over on it's side at one time or another, and I was no exception! One day upon leaving the stage I forgot to extend the wheels and when I went over the ramp underneath the large stage doors, over it went! Fortunately I wasn't fired for my mistake, but the sound department were obviously not happy with me for days after.

stage from the sound department. Thr Fisher boom was an instrument on wheels with a platform to stand on and an arm that extended several feet and at the end of it was affixed the microphone. The operator could control with ease the position of the microphone over the actors by extending the arm and swivelling the microphone to the correct angle of the emitting speaking voice. The wheels were like small car tyres and could extend or contract to fit through narrow areas. They had to be extended when being transported to and from the stage. Every assistant had had the harrowing experience of tipping the fragile boom over on it's side at one time or another, and I was no exception! One day upon leaving the stage I forgot to extend the wheels and when I went over the ramp underneath the large stage doors, over it went! Fortunately I wasn't fired for my mistake, but the sound department were obviously not happy with me for days after.

stage from the sound department. Thr Fisher boom was an instrument on wheels with a platform to stand on and an arm that extended several feet and at the end of it was affixed the microphone. The operator could control with ease the position of the microphone over the actors by extending the arm and swivelling the microphone to the correct angle of the emitting speaking voice. The wheels were like small car tyres and could extend or contract to fit through narrow areas. They had to be extended when being transported to and from the stage. Every assistant had had the harrowing experience of tipping the fragile boom over on it's side at one time or another, and I was no exception! One day upon leaving the stage I forgot to extend the wheels and when I went over the ramp underneath the large stage doors, over it went! Fortunately I wasn't fired for my mistake, but the sound department were obviously not happy with me for days after.

stage from the sound department. Thr Fisher boom was an instrument on wheels with a platform to stand on and an arm that extended several feet and at the end of it was affixed the microphone. The operator could control with ease the position of the microphone over the actors by extending the arm and swivelling the microphone to the correct angle of the emitting speaking voice. The wheels were like small car tyres and could extend or contract to fit through narrow areas. They had to be extended when being transported to and from the stage. Every assistant had had the harrowing experience of tipping the fragile boom over on it's side at one time or another, and I was no exception! One day upon leaving the stage I forgot to extend the wheels and when I went over the ramp underneath the large stage doors, over it went! Fortunately I wasn't fired for my mistake, but the sound department were obviously not happy with me for days after. Jock May (sound mixer) did not like me at all. Part of my job was to listen for the 'local' phone which was attached to the side of the mixer. It's major function was to signal to the recordist in the monitor room when to start the recorder. This was done by pressing a button on the phone once, Jock would then wait for two 'beeps' and this would indicate that the recorder was up to 'speed'. He would then motion to the assistant director, Ron Purdie, that the sound crew were ready and the camera crew could commence shooting. On one occasion I missed the phone ringing because I was talking to somebody, and this annoyed Jock greatly. As a result he told me that I should find another job and stay out of the sound department. Well fortunately, this didn't materialise as here I am forty years later still working in the sound department!

Another chore I had as a boom assistant was as a 'grip'. When actors walk from position a to b, which could be any distance, the camera and often the boom has to follow (track). This procedure was not easy. I had to first observe the position of the camera, which was on a 'dolly' a four-wheeled 'transport' which supports the heavy camera. The camera 'grip' can move forward, backward or sharply from side to side by simply turning the steering column handle. Camera tape or chalk marks are placed on the floor as a guide to actors and technicians showing where the camera will move. I then had to follow the camera and make sure I knew when the camera dolly was going to stop so I didn't bump into it. I recall this happened at least once. My wheels bumped into the camera dolly which sent a vibration through to the camera. The camera operator, observing the action through the viewfinder immediately called 'cut' when he felt the sharp movement. This was before the completion of the series and I thought I had been fired. Fortunately I was just re-assigned.

It was at this time that the ACTT Trade Union were reviewing my application and deciding whether or not to grant me membership. There were several people that were opposed to the idea. I have to thank Graham Hartstone, who I heard managed to sway the decision of the board into granting me membership. Graham was a sound technician at the time when I went to work at Pinewood in August '68 and he eventually was promoted to Dubbing Mixer and then as department head before he retired a few years ago.

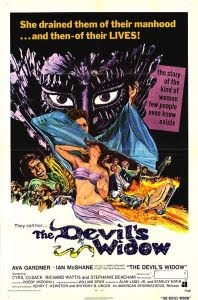

In August, '69 I was assigned as a boom assistant to a picture called Tam-Lin (The Devil's Daughter). This was the first production to utilise the new L & M Stages. These were identical in  design to J & K Stages, built on the opposite side of the studio right on the edge facing Black Park - a large heavily wooded area with a lake and large grass patches and long narrow rough unmade roads. This site is well known as a filming location, and Hammer Films (and Pinewood) used it on many of their productions. "Tam-Lin' was a production made by companies Commonwealth United and Winkast Productions (Jerry Gershwin & Elliot Kastner - who had produced "Where Eagles Dare" the previous year). The director was actor Roddy McDowall. The film had been on location in Scotland and had returned to the studio for filming interiors and other local areas. The sound crew were mixer Bill Daniels and the boom operator was Gus Lloyd. Together they had worked on many Pinewood productions. The continuity lady was Penny Daniels who was married to Bill. The production moved a lot slower compared to working on a TV series due to the more critical lighting methods, camera set-ups and longer rehearsals with the actors. Ava Gardner and Ian McShane were the main stars and the film's plot featured the opportunity for many young actors who would soon develop their own careers, including Stephanie Beacham, Joanna Lumley and Madeline Smith. Also featured were daughters of established players such as Jenny Hanley (daughter of Jimmy) and Sinead Cusack (daughter of Cyril).

design to J & K Stages, built on the opposite side of the studio right on the edge facing Black Park - a large heavily wooded area with a lake and large grass patches and long narrow rough unmade roads. This site is well known as a filming location, and Hammer Films (and Pinewood) used it on many of their productions. "Tam-Lin' was a production made by companies Commonwealth United and Winkast Productions (Jerry Gershwin & Elliot Kastner - who had produced "Where Eagles Dare" the previous year). The director was actor Roddy McDowall. The film had been on location in Scotland and had returned to the studio for filming interiors and other local areas. The sound crew were mixer Bill Daniels and the boom operator was Gus Lloyd. Together they had worked on many Pinewood productions. The continuity lady was Penny Daniels who was married to Bill. The production moved a lot slower compared to working on a TV series due to the more critical lighting methods, camera set-ups and longer rehearsals with the actors. Ava Gardner and Ian McShane were the main stars and the film's plot featured the opportunity for many young actors who would soon develop their own careers, including Stephanie Beacham, Joanna Lumley and Madeline Smith. Also featured were daughters of established players such as Jenny Hanley (daughter of Jimmy) and Sinead Cusack (daughter of Cyril).

design to J & K Stages, built on the opposite side of the studio right on the edge facing Black Park - a large heavily wooded area with a lake and large grass patches and long narrow rough unmade roads. This site is well known as a filming location, and Hammer Films (and Pinewood) used it on many of their productions. "Tam-Lin' was a production made by companies Commonwealth United and Winkast Productions (Jerry Gershwin & Elliot Kastner - who had produced "Where Eagles Dare" the previous year). The director was actor Roddy McDowall. The film had been on location in Scotland and had returned to the studio for filming interiors and other local areas. The sound crew were mixer Bill Daniels and the boom operator was Gus Lloyd. Together they had worked on many Pinewood productions. The continuity lady was Penny Daniels who was married to Bill. The production moved a lot slower compared to working on a TV series due to the more critical lighting methods, camera set-ups and longer rehearsals with the actors. Ava Gardner and Ian McShane were the main stars and the film's plot featured the opportunity for many young actors who would soon develop their own careers, including Stephanie Beacham, Joanna Lumley and Madeline Smith. Also featured were daughters of established players such as Jenny Hanley (daughter of Jimmy) and Sinead Cusack (daughter of Cyril).

design to J & K Stages, built on the opposite side of the studio right on the edge facing Black Park - a large heavily wooded area with a lake and large grass patches and long narrow rough unmade roads. This site is well known as a filming location, and Hammer Films (and Pinewood) used it on many of their productions. "Tam-Lin' was a production made by companies Commonwealth United and Winkast Productions (Jerry Gershwin & Elliot Kastner - who had produced "Where Eagles Dare" the previous year). The director was actor Roddy McDowall. The film had been on location in Scotland and had returned to the studio for filming interiors and other local areas. The sound crew were mixer Bill Daniels and the boom operator was Gus Lloyd. Together they had worked on many Pinewood productions. The continuity lady was Penny Daniels who was married to Bill. The production moved a lot slower compared to working on a TV series due to the more critical lighting methods, camera set-ups and longer rehearsals with the actors. Ava Gardner and Ian McShane were the main stars and the film's plot featured the opportunity for many young actors who would soon develop their own careers, including Stephanie Beacham, Joanna Lumley and Madeline Smith. Also featured were daughters of established players such as Jenny Hanley (daughter of Jimmy) and Sinead Cusack (daughter of Cyril). I worked on this film for almost two months and it was a happy experience all the way. We had a few interesting people visit the set. Among them were Allan Ladd Jnr. and Stanley Mann, both were either producer/writers on the film. Lee Remick also visited the set on one occasion. She was involved with our assistant director Kip Gowans and, if they weren't already, they would eventually marry. My duties were the same as on "Up She Goes\From A Birds Eye View". Occasionally a second microphone was required for odd dialog lines at a distance where the main boom mike could not access in time. On these occasions I would have to plant myself, often on the set eg. hidden behind a couch out of camera range holding a 'stick' with a microphone on the end.

Usually at the end of production there is always an 'end of production party' when all members of the cast and crew get together on one of the stages for a final get together. This was the only occasion that I had the opportunity for a brief conversation with Ava Gardner who was a very charming and lovely lady. These parties can often be an emotional time, as with long shooting schedules, people form close relationships. For some people these were colleges with whom they would never work with again.

Working on film and TV production, for most of the crew is a 'free-lance' career. Once the film is over you are unemployed and it could be months or the following Monday before you are employed again. In the 1960's the sound department, mixers, boom operators, sound camera recordists and boom assistants were 'on staff' studio employees. Eventually, as time went on they would also become free-lance. Fortunately my employment continued and I was moved over to Theatre #5 in October, '69 and remained there until Spring '74. This was the ADR / Foley recording theatre where post production dialogue and sound effects are recorded.

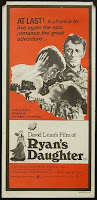

During my time there I met many actors and directors. For a 21/22 year-old film buff on the loose in a film studio, with so much activity and creativity going on, it was like being in a huge amusement park. Although the job was strict, during the quiet moments I could wander the  studio halls and stages. Although some of the sets were closed, e.g. "The Devils" most were not and at every opportunity I would witness the shooting and make friends at the same time. As I had mentioned in a previous post, I had seen "Lawrence of Arabia" in 70mm many times at the Metropole, Victoria in London and "Doctor Zhivago" at least twice in 70mm at the Empire, Leicester Square. The next Lean film was announced and was to be shot in Ireland. Months and weeks went by and "Michael's Day" as it was known then (later to be "Ryans Daughter"), was coming to the end of it's shooting schedule. There was no thought in my mind that the film would come to Pinewood for Post Production, I thought Shepperton would get the job as his last British based production ("Lawrence") was done there. It was early - mid 1970 and I was now working in Theatre 5 which dealt with the recording of dialog and sound effects. (I started as a Boom Assistant on the shooting stages and in late '69 moved into Theatre 5). One day, quite out of the blue it was announced that Pinewood would be handling all the Post Production chores. This meant that the editing crew would move into the studios' cutting rooms. David Lean and his editor Norman Savage had one room and the first and second assistants had the other. There were several sound editors headed by the legendary Winston Ryder. He and Lean went back many years together.

studio halls and stages. Although some of the sets were closed, e.g. "The Devils" most were not and at every opportunity I would witness the shooting and make friends at the same time. As I had mentioned in a previous post, I had seen "Lawrence of Arabia" in 70mm many times at the Metropole, Victoria in London and "Doctor Zhivago" at least twice in 70mm at the Empire, Leicester Square. The next Lean film was announced and was to be shot in Ireland. Months and weeks went by and "Michael's Day" as it was known then (later to be "Ryans Daughter"), was coming to the end of it's shooting schedule. There was no thought in my mind that the film would come to Pinewood for Post Production, I thought Shepperton would get the job as his last British based production ("Lawrence") was done there. It was early - mid 1970 and I was now working in Theatre 5 which dealt with the recording of dialog and sound effects. (I started as a Boom Assistant on the shooting stages and in late '69 moved into Theatre 5). One day, quite out of the blue it was announced that Pinewood would be handling all the Post Production chores. This meant that the editing crew would move into the studios' cutting rooms. David Lean and his editor Norman Savage had one room and the first and second assistants had the other. There were several sound editors headed by the legendary Winston Ryder. He and Lean went back many years together.

studio halls and stages. Although some of the sets were closed, e.g. "The Devils" most were not and at every opportunity I would witness the shooting and make friends at the same time. As I had mentioned in a previous post, I had seen "Lawrence of Arabia" in 70mm many times at the Metropole, Victoria in London and "Doctor Zhivago" at least twice in 70mm at the Empire, Leicester Square. The next Lean film was announced and was to be shot in Ireland. Months and weeks went by and "Michael's Day" as it was known then (later to be "Ryans Daughter"), was coming to the end of it's shooting schedule. There was no thought in my mind that the film would come to Pinewood for Post Production, I thought Shepperton would get the job as his last British based production ("Lawrence") was done there. It was early - mid 1970 and I was now working in Theatre 5 which dealt with the recording of dialog and sound effects. (I started as a Boom Assistant on the shooting stages and in late '69 moved into Theatre 5). One day, quite out of the blue it was announced that Pinewood would be handling all the Post Production chores. This meant that the editing crew would move into the studios' cutting rooms. David Lean and his editor Norman Savage had one room and the first and second assistants had the other. There were several sound editors headed by the legendary Winston Ryder. He and Lean went back many years together.

studio halls and stages. Although some of the sets were closed, e.g. "The Devils" most were not and at every opportunity I would witness the shooting and make friends at the same time. As I had mentioned in a previous post, I had seen "Lawrence of Arabia" in 70mm many times at the Metropole, Victoria in London and "Doctor Zhivago" at least twice in 70mm at the Empire, Leicester Square. The next Lean film was announced and was to be shot in Ireland. Months and weeks went by and "Michael's Day" as it was known then (later to be "Ryans Daughter"), was coming to the end of it's shooting schedule. There was no thought in my mind that the film would come to Pinewood for Post Production, I thought Shepperton would get the job as his last British based production ("Lawrence") was done there. It was early - mid 1970 and I was now working in Theatre 5 which dealt with the recording of dialog and sound effects. (I started as a Boom Assistant on the shooting stages and in late '69 moved into Theatre 5). One day, quite out of the blue it was announced that Pinewood would be handling all the Post Production chores. This meant that the editing crew would move into the studios' cutting rooms. David Lean and his editor Norman Savage had one room and the first and second assistants had the other. There were several sound editors headed by the legendary Winston Ryder. He and Lean went back many years together. In a matter of days, appointments were made for the recording of the sound effects and post dialog or ADR. We called it the virgin loop system, 'looping'. This consisted of a small amount of the picture cut into a loop. The corresponding production soundtrack was cut to match match. A piece of 35mm unrecorded magnetic film was also cut into a loop and the three pieces of film ran syncronised or interlocked together. The actor would look at the picture loop projected up on the screen while listening to the 'guide track' on a headphone. He will then record his voice onto the magnetic film and try to match it to his lips on the screen. The sound editor, who is supervising the session will tell the actor when he has succeeded in getting the 'sync' and the performance right. The sound editor will then take the newly recorded sound back to the cutting room and refine the sync further with the picture.

The music, it was decided, would be recorded at Denham Studios. There were no music recording facilities at Pinewood. Cyril Crowhurst, who was Pinewood's Sound Department superviser oversaw the installation of a proper scoring stage at Denham in 1946. Denham and Pinewood were two massive studios built in the mid thirties and during the second world war Denham continued to shoot films while Pinewood war used more for storage and other war related missions. After the war in 1945 the two studios used each others facilities and the credit on many productions displayed the D and P logo. The Denham scoring stage, in 1966, was taken over by Ken Cameron's company Anvil, who were formerly at a small studio by the name of Beaconsfield. Ken Cameron was an expert in recording, especially in music. He made his name in the forties and fifties creating soundtracks for many shorts and documentaries. Among his many clients were Hammer Films of which all the classic gothic soundtracks were created there at Beaconsfield. As Ken was drawing close to retiring age he hired Eric Tomlinson who was at the time working at CTS in Bayswater London. Eric was the scoring mixer on "Ryan's Daughter" scheduled to be recorded in July, 1970.

By this time I had met David Lean and all the cutting crew. I wanted to be as close to every aspect of the production as possible, knowing it would probably be years before he decided  on making another film. (Thanks to the mouth of critic Pauline Kael, little did I know just how long that would be!) When I heard that the scoring sessions were scheduled I approached editor Norman Savage and asked him if it was possible to attend. A few days later he came to me and said that he spoke to David and said that it would be okay. I then proceeded to book my vacation/holiday time to correspond with the sessions. I spent a whole week over at Anvil, Denham. I had a chair immediately behind the podium. Prior to this I had heard that Jarre was doing the score and that he was to conduct. It was a thrilling experience. I spent five days on the stage. Behind me was the recording room where I could see Eric Tomlinson, the mixer. David Lean attended every day. He always took the time to smile and say good morning to me. The orchestra was overwhelming. Immediately in front of the orchestra were nine harpists a mike hung over groups of three, representing left, center and right, when it came to record the Overture. Monique Rollin, a very attractive blonde lady, played the zither. I made a point of introducing myself to her as her playing was a big part of "Lawrence" and "Zhivago". One day one of the nine harpists left at lunch and didn't return, this was the only time I saw Maurice lose his temper! He was very pleasant toward me and expressed amazement that I would want to spend all my vacation time on a recording stage.

on making another film. (Thanks to the mouth of critic Pauline Kael, little did I know just how long that would be!) When I heard that the scoring sessions were scheduled I approached editor Norman Savage and asked him if it was possible to attend. A few days later he came to me and said that he spoke to David and said that it would be okay. I then proceeded to book my vacation/holiday time to correspond with the sessions. I spent a whole week over at Anvil, Denham. I had a chair immediately behind the podium. Prior to this I had heard that Jarre was doing the score and that he was to conduct. It was a thrilling experience. I spent five days on the stage. Behind me was the recording room where I could see Eric Tomlinson, the mixer. David Lean attended every day. He always took the time to smile and say good morning to me. The orchestra was overwhelming. Immediately in front of the orchestra were nine harpists a mike hung over groups of three, representing left, center and right, when it came to record the Overture. Monique Rollin, a very attractive blonde lady, played the zither. I made a point of introducing myself to her as her playing was a big part of "Lawrence" and "Zhivago". One day one of the nine harpists left at lunch and didn't return, this was the only time I saw Maurice lose his temper! He was very pleasant toward me and expressed amazement that I would want to spend all my vacation time on a recording stage.

on making another film. (Thanks to the mouth of critic Pauline Kael, little did I know just how long that would be!) When I heard that the scoring sessions were scheduled I approached editor Norman Savage and asked him if it was possible to attend. A few days later he came to me and said that he spoke to David and said that it would be okay. I then proceeded to book my vacation/holiday time to correspond with the sessions. I spent a whole week over at Anvil, Denham. I had a chair immediately behind the podium. Prior to this I had heard that Jarre was doing the score and that he was to conduct. It was a thrilling experience. I spent five days on the stage. Behind me was the recording room where I could see Eric Tomlinson, the mixer. David Lean attended every day. He always took the time to smile and say good morning to me. The orchestra was overwhelming. Immediately in front of the orchestra were nine harpists a mike hung over groups of three, representing left, center and right, when it came to record the Overture. Monique Rollin, a very attractive blonde lady, played the zither. I made a point of introducing myself to her as her playing was a big part of "Lawrence" and "Zhivago". One day one of the nine harpists left at lunch and didn't return, this was the only time I saw Maurice lose his temper! He was very pleasant toward me and expressed amazement that I would want to spend all my vacation time on a recording stage.

on making another film. (Thanks to the mouth of critic Pauline Kael, little did I know just how long that would be!) When I heard that the scoring sessions were scheduled I approached editor Norman Savage and asked him if it was possible to attend. A few days later he came to me and said that he spoke to David and said that it would be okay. I then proceeded to book my vacation/holiday time to correspond with the sessions. I spent a whole week over at Anvil, Denham. I had a chair immediately behind the podium. Prior to this I had heard that Jarre was doing the score and that he was to conduct. It was a thrilling experience. I spent five days on the stage. Behind me was the recording room where I could see Eric Tomlinson, the mixer. David Lean attended every day. He always took the time to smile and say good morning to me. The orchestra was overwhelming. Immediately in front of the orchestra were nine harpists a mike hung over groups of three, representing left, center and right, when it came to record the Overture. Monique Rollin, a very attractive blonde lady, played the zither. I made a point of introducing myself to her as her playing was a big part of "Lawrence" and "Zhivago". One day one of the nine harpists left at lunch and didn't return, this was the only time I saw Maurice lose his temper! He was very pleasant toward me and expressed amazement that I would want to spend all my vacation time on a recording stage. At this time Ken Cameron was taking care of administrative duties relating to the stage and as a consultant. He had a tiny office. He was a Scotsman and always wore a kilt. He also loved his whiskey! Like the rest of the 'old school gentlemen' of the British Film Industry, they were always well educated and well dressed and always had time to talk to you if they knew you were genuinely interested. Several days were spent recording the sound effects and footsteps (foley). We were informed by the editors that this was to be a stereo soundtrack as the procedures for recording are very different to a mono film. No stereo or multiple miking was used. All the main foreground characters on the screen were recorded separately so that during the final mix there could be total control on each character's footsteps as they moved across the three speaker positions on the screen. The background crowd footsteps were done in two ways. Groups of feet movement for the left, center and right side of the screen. Also a track of footsteps would be recorded that would be panned back and forth between speakers. Sound effects and crowd voices were recorded in the same manner. This particular soundtrack was to be a four-track stereo mix, three channels behind the screen and the fourth channel would be for the mono surrounds.

During this time two events happened involving "Lawrence of Arabia". In England, the film was re-issued in it's cut 202 minute UK version at the Dominion, Tottenham Court Road. David and I had a brief discussion about the color of this revival print in the men's toilet of all places outside Theatre 2's dubbing theatre! The other 'event' was that while he was cutting "Ryan" he spent several days over at Shepperton Studios, at the request of Columbia Pictures, removing a further 30 minutes out of "Lawrence" for the US only. The main mixing of "Ryan's Daughter" went very smoothly. By this time I knew Gordon McCallum, the dubbing mixer, very well and spent every available moment I had in the theatre during the pre-mixing of the dialog, efx and music. David Lean came in often and the two of them had many quite discussions on how he wanted the film to sound like. (Lean and McCallum were not strangers to each other. McCallum's career stretches back to the 40's and he had dubbed several of Lean's films). Often it would be just the three of us, other times many of the sound editors would be in attendance when their work was being mixed.

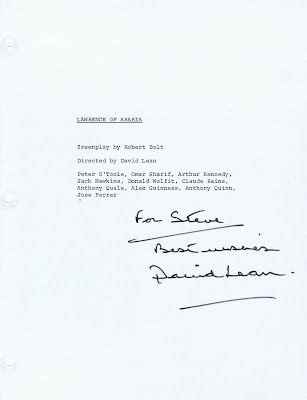

I think that during all this time I only once went into David Lean's editing room and this was to collect some LP's of David's films that I asked Norman if he would have him sign. It took several days and often when I would return from the studio bar at lunchtime, after a drink, I would take a short cut through the executive restaurant and there at a table by the window David would be sitting on his own having his lunch, and as I passed by he would say hello and remind me that he had not forgotten to sign my LP's. Moments like these I will never forget.

Here is Stephen's copy of the Lawrence of Arabia script that David Lean signed for him:

On one Sunday morning, a week or two before the premiere, I attended the Empire, Leicester Square for a test run for sound. Gordon McCallum was present and requested some equalisation of the theatre's sound system. The four-track mix had been artificially spread by Technicolor London's special technique as this was a 70mm roadshow release.This brought to an end my personal relationship with "Ryan's Daughter". The film, now, was ready to be presented to the world.

On one Sunday morning, a week or two before the premiere, I attended the Empire, Leicester Square for a test run for sound. Gordon McCallum was present and requested some equalisation of the theatre's sound system. The four-track mix had been artificially spread by Technicolor London's special technique as this was a 70mm roadshow release.This brought to an end my personal relationship with "Ryan's Daughter". The film, now, was ready to be presented to the world. By this time I was a member of ACTT, and had ambitions to get involved in the more creative side of film-making, which was the cutting rooms. During my time in Theatre 5, I knew many picture and sound editors and assistants. Once again I had hit another kind of brick wall. Most editors, all which are free-lance, usually keep their assistants when they move from film to film. So I ended up seeking a trainee assistant editor's position in a company, probably based in London. This, of course meant me leaving pinewood, which I knew would have to happen at some point. I wanted to be a second assistant picture editor, free-lance which would involve the opportunity to work at any of the major studios such as ABPC and Shepperton.

Eventually, luck came my way. A position opened up in early 1974, around the time that "The Man With The Golden Gun" started shooting, at a company called De Lane Lea in Wardour Street, London. The company was started by french producer Jacques De Lane Lea. So I left the vast studio behind me to work in the top floor offices which were converted into cutting rooms.

As always, a big thank you to Stephen for sharing his memories of his career with us.

Piley